If you’re not sure that bilateral tubal ligation is the right surgery for you, please read the female sterilization procedures overview page.

On this page, we discuss the bilateral tubal ligation in the context of pre-surgery, during surgery, post-surgery, and recovery. Follow the linked pages to find out more detailed information.

Overview

Bilateral tubal ligation (BTL) is the most common method to sterilize women. It’s a procedure that doctors can only prescribe with the goal of sterilization; it doesn’t have any other health benefits—such as reducing the risk of certain cancers.

Bilateral tubal ligation (BTL) is the most common method to sterilize women. It’s a procedure that doctors can only prescribe with the goal of sterilization; it doesn’t have any other health benefits—such as reducing the risk of certain cancers.

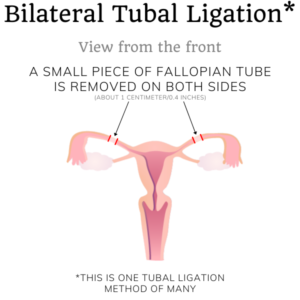

Bilateral means on both sides of the body (left and right). Tubal means with regards to the fallopian tubes. Ligation means to bind or tie. Sometimes, doctors call this procedure bilateral tubal occlusion. Occlusion means to obstruct. So we end up with a procedure that binds or obstructs the passageway of the fallopian tubes on both sides of your body.

Doctors perform this surgery in almost every country on earth, but it doesn’t look the same everywhere. The options you’ll have for surgery and occlusion methods will depend on the hospital and even the doctor you choose. The general rule is: if you choose a better hospital with a highly-trained doctor and pay more, you will have less time under anesthesia, less recovery time, and fewer scars. This isn’t a perfect rule, since you can also pay a lot for bad healthcare.

Bilateral tubal ligation is also the only female sterilization method that is somewhat reversible. Some tube-tying methods are more reversible than others. Here at SterilizationAunty, we regard high reversibility as a disadvantage of the tube-tying method. This is because a highly-reversible method correlates to higher failure rates in the form of unintended (ectopic) pregnancies. Reversibility is not an advantage if you’re sure you want to be sterile. Do not seek out bilateral tubal ligation if you might want to become pregnant later.

Note: if you are pregnant and want this to be your last pregnancy, you can also undergo a bilateral tubal ligation right after giving birth. You must also have discussed this with your doctor prior to giving birth. This will look different from how this page describes bilateral tubal ligation down below.

Undergoing bilateral tubal ligation surgery

Read our guide for what to do for and expect of your female sterilization surgery here.

While you’re unconscious from the general anesthetic, your surgeon will begin your bilateral tubal ligation. This begins with making the incisions for either laparoscopic surgery or for laparotomy.

The duration of your surgery depends on a few factors. A laparoscopic tubal ligation will take about 20-30 minutes while the same procedure via laparotomy takes 30 minutes or more1. As a general rule, less time spent under general anesthesia is better for you.

If you’ve chosen a laparoscopic bilateral tubal ligation, the surgeon will make a small incision in your navel and a small second (and possibly third) incision below your bikini line. If you’ve chosen a bilateral tubal ligation by laparotomy, your surgeon will make a longer incision below your bikini line. You can find more information about laparoscopic approaches on the page that compares surgical incisions.

Once your surgeon has a good view of your womb, your ovaries, and your fallopian tubes, they will begin the sterilization procedure. Your surgical team uses various tools to grab your fallopian tubes, hold them down, cut, and close them.

Methods to tie or close the fallopian tubes

Once your surgeon has access to your fallopian tubes, there are a few ways to block the egg cell’s passageway between your ovaries and womb. Before your surgery, you should ask your doctor which method they will use. The following are the most common way to perform a tubal ligation:

Once your surgeon has access to your fallopian tubes, there are a few ways to block the egg cell’s passageway between your ovaries and womb. Before your surgery, you should ask your doctor which method they will use. The following are the most common way to perform a tubal ligation:

Ligation

The original method to perform a tubal ligation is by tying off (ligating) parts of a tube and then cutting it, removing a piece, and closing it. Because it also removes a small part of the tube, one can also call it a partial bilateral salpingectomy. The section removed is usually about 1 cm (0.4 in) or more. A longer section removed correlates to lower failure rates. The more tube your surgeon removes, the more your risk at ovarian cancer is reduced.

One technique (the Pomeroy) makes a loop of the tube, ties it with suture, then cuts out the loop. Since the suture is made of an absorbable material, the body will break it down and the tube ends will move apart over time. Another technique (the Parkland) ties off two sections of the tube with suture, then cuts out the piece in between, resulting in an immediate gap between the two ends of the fallopian tube2.

Both of these techniques are not very difficult for a surgeon, can be done fast, and are very effective. Their failure rate is very low because a whole section of the tube is removed. There are other surgical techniques3 with different levels of complication and failure, but they are less common.

Electrosurgery

Electrosurgery is the use of a tool with an electrical current to cut, seal, and destroy sections of the fallopian tubes. Not all hospitals offer this method, since it requires special equipment. The advantage of electrosurgery is that the tool cuts and closes at the same time, which prevents blood loss. Its small risks include unintended burns and inhaling surgical smoke. Your surgeon will need to know if there are any metal objects in your body before surgery, which is confirmed by x-ray.

There are two different tools to perform electrosurgery: unipolar coagulation and bipolar coagulation. Over the years, bipolar coagulation has replaced much of unipolar coagulation because it reduces the risk of injury from heat. However, the failure rate of bipolar coagulation is slightly higher than that of unipolar coagulation2. Researchers and surgeons working on failure reduction learned that the failure rate drops significantly if three or more locations of the tube are coagulated with electrosurgery4.

There are two different tools to perform electrosurgery: unipolar coagulation and bipolar coagulation. Over the years, bipolar coagulation has replaced much of unipolar coagulation because it reduces the risk of injury from heat. However, the failure rate of bipolar coagulation is slightly higher than that of unipolar coagulation2. Researchers and surgeons working on failure reduction learned that the failure rate drops significantly if three or more locations of the tube are coagulated with electrosurgery4.

Mechanical methods: clips or rings

Clips and rings are mechanical devices metal objects that squeeze the fallopian tube shut and do not destroy or remove segments. They are non-magnetic and will show up in X-rays. Since they don’t damage the tube so much, clips are the most reversible form of tubal ligation.

There are four main mechanical devices: Filshie clip, Hulka-Clemens clip, and silastic rings or bands, such as the Falope ring and Yoon ring. These are made of different materials, such as plastic, titanium, stainless steel (which might contain nickel), gold, and silicone rubber5. If you already know you have an allergy to one or more of these components, it might be best to choose a different occlusion method. Your surgeon will obviously ask you about allergies before using any of these methods.

Over time, these devices can also ‘migrate’ along the tube from their original position. The failure rate of all methods is highest with Hulka clips, followed by rings and bands2.

Findings during your surgery

Your anatomy is unique. Because your surgeon doesn’t know what they’ll find once they begin the operation, the surgery might turn out a little different than anticipated. For example, if your surgeon finds a cyst on your fallopian tube, they might cut out a larger section of one of the fallopian tubes and send the cyst to pathology for examination. Your doctor will have to make this decision during the operation to the best of your interests. You can inquire after the operation if it went as expected or if your surgeon needed to improvise a little.

Your anatomy is unique. Because your surgeon doesn’t know what they’ll find once they begin the operation, the surgery might turn out a little different than anticipated. For example, if your surgeon finds a cyst on your fallopian tube, they might cut out a larger section of one of the fallopian tubes and send the cyst to pathology for examination. Your doctor will have to make this decision during the operation to the best of your interests. You can inquire after the operation if it went as expected or if your surgeon needed to improvise a little.

The failure rate and pregnancy risk

There is a small risk that your bilateral tubal ligation fails and you’ll fall pregnant. Such a pregnancy is very likely to be ectopic, which might require another surgery to remove the unviable pregnancy. Rarely, the pregnancy is not ectopic and is viable to carry to term 2.

Across all surgery methods and occlusion methods, the cumulative failure rate of bilateral tubal ligation stands at about 1%6. Most tubal failure pregnancies occur within five years of the surgery. There is no difference in failure rate between a laparoscopic approach and a (mini-) laparotomy7.

The failures that occur within one year of the surgery are mostly due to improper procedure8. This means that the surgeon didn’t follow the guidelines precisely, often due to inexperience9. This can qualify as ‘medical negligence’ and will make it easier for you to undergo a re-sterilization procedure (which might be a different method from a bilateral tubal ligation).

As a general rule, the failure rate is higher in women without children than women who have given birth. This is especially true when a tubal ligation is done in the first 48 hours postpartum since the tubes are easily accessible in this timeframe2. The younger you are when undergoing tubal ligation, the higher the chance of failure. This is logical because younger women are fertile for more years and their bodies have more time to find alternate ways to regenerate a pathway7.

As more time passes, the body has a chance to find a way to ‘rebuild’ the tube. This accident can happen in two ways: spontaneous recanalization and tubo-peritoneal fistula7. During spontaneous recanalization, the connection of the tube becomes restored through the obstruction. Tuboperitoneal fistula is an abnormal connection between the tubes and the membrane that lines the abdominal cavity. Your surgeon is not to blame when this happens, since it’s just your body trying to ‘heal’ itself.

It’s good to remember that all these failures are very rare. There are no contraception methods that have more than the 99% effectiveness of a tubal ligation 6.

Risks and contraindications

Since bilateral tubal ligation is abdominal surgery, it comes with a few rare risks and contraindications. All these risks are due to the surgery and anesthesia. The tubal ligation procedure itself doesn’t add any significant risk. Read our page about risks, contraindications, and side effects to learn more.

Since bilateral tubal ligation is abdominal surgery, it comes with a few rare risks and contraindications. All these risks are due to the surgery and anesthesia. The tubal ligation procedure itself doesn’t add any significant risk. Read our page about risks, contraindications, and side effects to learn more.

Conclusion

We hope this page gave you a good overview of the different methods of bilateral tubal ligation and their advantages and disadvantages. If you have any questions, don’t hesitate to send us a message.

- Source: Planned Parenthood: What can I expect if I get a tubal ligation?[↩]

- Source: Engender Health (2002) Contraceptive Sterilization: Global Issues and Trends. Download the chapter here[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Source: Sciarra, J.J. (2004) Surgical Procedures for Tubal Sterilization[↩]

- Source: Peterson, H.B., Xia, Z., Wilcox, L.S., Tylor, L.R. and Trussell, J. (1999) Pregnancy after tubal sterilization with bipolar electrocoagulation[↩]

- Source: The Clip Project: Is it a Filshie or Hulka Clip?[↩]

- Source: Planned Parenthood[↩][↩]

- Source: Varma, R. and Gupta, J.K. (2004) Failed sterilisation: evidence‐based review and medico‐legal ramifications[↩][↩][↩]

- Source: Date, S.V., Rokade, J., Mule, V., and Dandapannavar, S. (2014) Female sterilization failure: Review over a decade and its clinicopathological correlation[↩]

- Source: Hughes, G.J. (1977) Sterilisation failure[↩]